As the digital age continues to evolve, child sexual abuse has taken on new dimensions online. In a press release in May 2022, the European Commission revealed that in 2021, 85 million images and videos of child sexual abuse were reported globally. This alarming statistic underscores how pervasive this issue is, prompting the European Commission to take decisive action in response.

On 11 May 2022, the European Commission has proposed a new piece of legislation known as the Regulation to Prevent and Combat Child Sexual Abuse (Child Sexual Abuse Regulation, or CSAR). The key provision of this new legislation would require online platforms to detect the content of their platforms for instances of child sexual abuse material, on the basis of detection orders received from law enforcement agencies.

However, this provision has been heavily opposed by privacy and human rights protection organizations. These groups argue that the implementation of CSAR would inevitably violate user privacy, particularly by undermining end-to-end encryption (E2EE), which has become a vital tool for online security and privacy.

In contrast, child protection organizations who have a vested interest in the well-being of vulnerable children, strongly support the CSAR. They argue that user privacy protection and child protection can co-exist and measures such as detection orders are necessary to prevent the spread of child sexual abuse material online.

The conflicts between child protection and user privacy protection are multifaceted. This article will try to offer an in-depth analysis of the perspectives of both parties for a comprehensive understanding of the issue.

1. Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation as a Global Phenomenon

With the boom of the Internet, child sexual abuse and exploitation has become more serious worldwide. According to the definition of The Children’s Society, a British charity, child sexual abuse refers to “when a child or young person is forced or tricked into sexual activities”, while child sexual exploitation refers to “a type of sexual abuse when an adult tricks a child into performing sexual acts by offering them something. This might include gifts, drugs, money, status or even affection”. When child sexual exploitation happens, the abuser may manipulate children and young people into sending them sexually explicit images, having sexual conversations, or filming and streaming sexual activities.

Since 1998, CyberTipline, established by National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), has accepted hundreds of millions of images involving online child sexual abuse materials (CSAM) reported by the public or by online platforms. NCMEC staff have reviewed these reports and tried to locate exploited children. They then assist law enforcement agencies in rescuing them.

In 2022, CyberTipline has received more than 32 million reports from around the world of suspected child online sexual exploitation, including child sex trafficking, child sexual molestation, unsolicited obscene material sent to a child, and online enticement of children for sexual acts. More than 99.5% of these reports is suspected to involve the possession, production, and distribution of CSAM.

Source: CyberTipline

In February-March 2018, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), a UK-based child protection charity, conducted a survey on children’s online experiences. The survey, which gathered responses from 40,000 children aged 7-16, found that 6% of those who had livestreamed had been requested to undress or change their clothing.

In EU countries, a recent EU report on fighting crimes has shown 684 incidents of child sexual exploitation were reported in 2022. 60 investigations were carried out, while only 30 suspects were arrested.

The human rights channel of the Council of Europe reveals alarming figures: about one in five children in Europe are victims of some form of sexual violence, including sexual harassment, rape, grooming, exhibitionism etc.; between 70% and 85% of abused children know their abusers, most of whom are people they trust; about 1/3 of abused children never tell anyone because of shame, guilt, fear, ignorance of the abuse or confusion —- Some children even believe they are in a true “relationship”.

Source: Council of European Union

2. Detection Orders of CSAR

In response to address the proliferation of CSAM online, on 11 May 2022 the European Commission adopted the Regulation to Prevent and Combat Child Sexual Abuse. In a press release on the same day, the Commission pointed out that “voluntary detection and reporting by digital companies has proved insufficient”, “A clear and binding legal framework is needed”. However, CSAR has been highly controversial and its legislative process is still ongoing.

CSAR will oblige online service providers to assess and mitigate the risk of misuse their services for child sexual abuse, and to detect, report and remove CSAM on their services. One of the hottest debates centers on detection orders (Articles 7-11).

Source: EUR-Lex

According to these five articles, the Coordinating Authorities (CAs) shall have the power to request the competent judicial authority or independent administrative authority to issue a detection order requiring a provider of hosting services or a provider of interpersonal communications services (e.g., Instagram, Facebook, hereinafter referred to as “provider”) to detect online child sexual abuse on a specific service.

National CAs shall be designated by the Member State. They are responsible for the implementation of the CSAR, including “the initiating and supervising the imposition of detection, blocking and removal processes, cooperating with CAs across the EU and coordinating at national level all efforts related to child sexual abuse”.

When initiating the detection process, the CAs shall establish a draft request for the issuance of a detection order, specifying the main elements of the content of the detection order they intend to request and the reasons for requesting it. And then they shall submit the draft request to the provider and the EU Center. Subsequently, the CAs shall consider any comments provided by the provider’s and the EU Center.

If the CAs determine that there is still evidence indicating a significant risk of child abuse, and that the reasons for issuing a detection order outweigh the potential negative consequences, they shall re-submit the draft request to the provider. The provider, in turn, shall draft an implementation plan within a reasonable time period set by the CAs.

Where the detection involves high-risk processing, or relating to child online grooming, the provider must conduct a data protection impact assessment and consult the data protection authorities. If, after regarding the implementation plan of the provider and the opinion of the data protection authority, the CAs confirm the risk again, they shall then submit the request for the issuance of detection orders to the competent judicial authority or independent administrative authority.

The authorities receiving the request must reassess the case before it issues the detection order. Once an order is issued, the provider must detect CSAM on their services.

3. EDRi’s Objections to Detection Orders

European Digital Rights (EDRi), a non-profit international advocacy organization for the protection of human rights and freedoms, has been one of the strongest opponents of the CSAR since 2022.

In October 2022, EDRi published a position paper entitled “A safe internet for all: upholding private and secure communication”. This paper analysed the background to the adoption of the CSAR, the EU legal framework, the key provisions of CSAR, and provides conclusions and recommendations.

In May 2023, EDRi further summarized the key points of the paper in a 26-page booklet. In this booklet, EDRi strongly criticizes detection orders, arguing that the detection would inevitably violate users’ privacy rights.

Source: EDRi

EDRi identifies three types of content that may be required to be detected – known CSAM, new CSAM and child sexual grooming. It claims that there are problems with the method used to detect each of these.

(1) Known CSAM

Known CSAM is usually referred to the images and videos which have been already reported, reviewed and put into hash database. A hash is a function that takes in an input (or “message”) and produces a fixed-size string of characters. Hash functions are designed to be one-way, meaning it should be computationally infeasible to reverse the process and obtain the original input.

The process for detecting known CSAM involves scanning content on online platforms, such as messages, and comparing it to the content in a hash database. If a successful match is found, the scanned content is known CSAM.

EDRi questions the accuracy of detection technologies, which may not be as precise as their developers claimed. In the Impact Assessment accompanying CSAR, the Commission explains the assessment of the accuracy is based on the data provided by developers, meaning there is no independent verification of the accuracy.

Furthermore, according to a Freedom of Access to Information (FOIA) request made by EDRi members, the Commission confirms that it bases its accuracy assessment on industry claims, and there is no independent third-party verification.

(2) New CSAM

New CSAM refers to content that has not previously been reported as CSAM or added into a hash database. Detecting new CSAM relies on AI-based technologies, such as nudity detection, which have been trained to distinguish between CSAM and non-CSAM. EDRi argues that such tools will flag any material that mactches the nudity or other search criteria as CSAM, such as photos of children bathing or adults in bikinis.

EDRi first criticizes the PhotoDNA technology, which the Commission considers to be extremely accurate. PhotoDNA is developed by Microsoft and is one of the primary technologies currently used to detect CSAM. According to data released by LinkedIn in 2021, out of 75 files that were identified as CSAM by PhotoDNA, only 31 of them were confirmed to be CSAM. This implies that the accuracy rate of this technology is only 41%.

Based on the data released by Meta Platforms Ireland Limited in February 2022, EDRi emphasizes that in less than two months, the detection technologies incorrectly reported 207 Facebook and Instagram accounts for spreading CSAM, leading to the deletion of these accounts. Additionally, there are thousands of users who are still appealing for their accounts to be reinstated.

The consequences of false reports can be severe. EDRi cites an article published by the New York Times on August 21, 2022, which mentions a father who took naked photos of his son to seek medical advice. These photos and videos were automatically backed up to Google Cloud storage. Two days later, his Google account was disabled because these photos and videos were flagged as CSAM. He lost contact with all of his friends and colleagues, as well as all of the photos of his son since he was one year old. The father was also under investigation by the local police.

(3) Child Sexual Grooming

Child grooming occurs when someone builds emotional connections with children or their families to gain their trust and then sexually abuse them. AI-based language analysis and probability techniques are used to detect signs of child grooming, such as text, audio, or other behaviors. The AI technologies are trained to study existing patterns of child grooming.

Similar to its position on the new CSAM detection technologies, EDRi maintains that AI-based child grooming detection strategies can also lead to false positives. Additionally, EDRi highlights the fact that the interpretation of child grooming is highly context-dependent, and that the definition of grooming can vary across EU countries due to different regulations on the legal age of sexual consent.

These facts make it more difficult for AI-based technologies to detect grooming. Even the most sophisticated Machine Learning-based Natural Language Processing (ML-NLP) models struggle with tasks such as comprehending emotions, grasping contextual meaning, and identifying keywords in text.

The above criticisms focus on the accuracy of detection technologies and the consequences of false positives. EDRi also emphasizes the impact of detection orders on end-to-end encryption (E2EE).

E2EE is a secure communication technique that guarantees the privacy and confidentiality of data shared between two parties. In an E2EE system, data remains encrypted in transit, meaning that even service providers or intermediaries do not have access to the actual content of the data. Popular communication tools like WhatsApp and Signal use E2EE by default to protect user conversations and calls.

EDRi maintains that while the CSAR may specify detection measures for specific instances, platforms are still responsible for scanning all user content, including E2EE content, to identify CSAM. Since the CSAR does not exempt E2EE content from detection, it fundamentally undermines the security of E2EE.

This is because the known methods for detecting E2EE content either weaken encryption or require the use of client-side scanning (CSS). CSS involves scanning data on devices like phones and computers at one end of the communication, either before encryption or after decryption. It has been criticized by network security and human rights advocates.

EDRi cites a report on privacy protection and E2EE published in September 2022 by Privacy International (PI), a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting privacy rights. The report states that CSS allows law enforcement to remotely search users’ devices by comparing their data with information stored on remote servers.

To detect CSAM, it scans all E2EE content, resulting in mass surveillance. The surveillance is “likely to have a significant chilling effect on free expression and association, with people limiting the ways they communicate and interact with others and engaging in self-censorship.”

Source: Privacy International

4. ECLAG’s Support for Detection Orders

In April 2022, a coalition of 65 non-governmental organizations, including the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) and the European child protection organization Eurochild, established the European Child Sexual Abuse Legislation Advocacy Group (ECLAG). The group, a strong supporter of CSAR, works to ensure that child rights are prioritised in EU digital and social policy.

In October 2023, ECLAG released a report aimed at addressing concerns about privacy raised by opponents of CSAR. The report directly responds to opponents’ concerns about detection orders:

Source: Child safety in Europe

Firstly, regarding the accuracy of the detection technologies, ECLAG cites the Impact Assessment report presented by the global consultancy Ecorys. The report shows that current technologies for the detection of new CSAM have an accuracy rate well above 90%, while for the grooming detection, the accuracy rate before human review is 88%.

On 24 October 2023, ECLAG member Eurochild emphasized in an opinion article that advanced detection technologies, including Thorn’s Safer Tool and Google’s Content Safety API, are currently being used to ensure security and privacy.

Safer Tool uses hash database matching and AI technologies to identify known CSAM and new CSAM separately. The identified content, after manual review, can be directly reported to the relevant online reporting hotlines.

The Content Safety API, based on AI technologies, is specifically designed to detect images that may contain new CSAM. It categorizes these images into different levels of priority, with higher priority indicating a higher likelihood of containing CSAM. Platforms using the Content Safety API can prioritize images for manual review based on the information it provides..

Secondly, in response to the claims that detection technologies would undermine E2EE, ECLAG notes that privacy-protective detection technologies, like CSS, already exist. For example, WhatsApp automatically checks for suspicious URLs on the user’s client side via CSS, preventing malicious URLs from spreading through its encrypted messaging service without compromising E2EE.

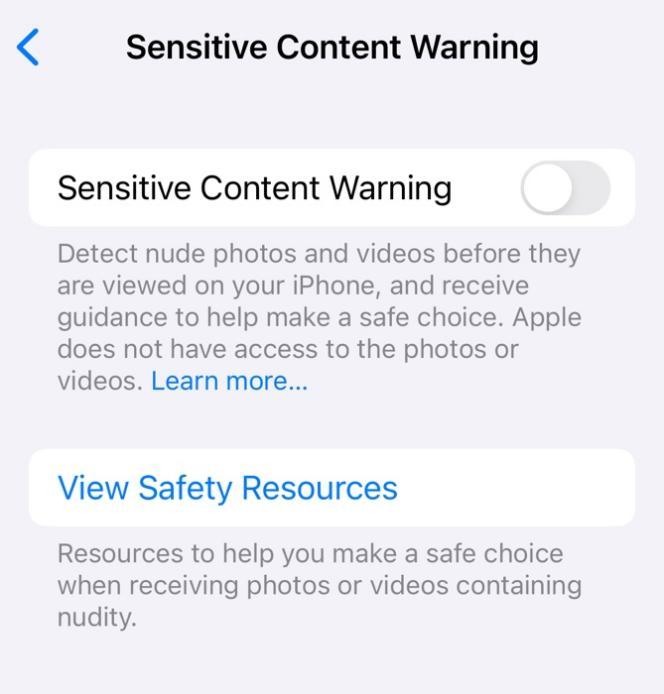

Browsers such as Chrome and Edge do the same to warn users when they navigate to dangerous websites or downloads. Apple has also introduced Sensitive Content Warning and Communication Safety, a tool that scans local messages on children’s devices and flags messages that contain explicit content.

Source: iPhone “Settings”

Thirdly, ECLAG points out that the claim that “the Regulation would unleash mass surveillance and ‘read’ all messages” is based on unfounded fears and on a misunderstanding of the technologies and the process. CSAR involves a comprehensive procedure of risk assessment, reviews, multiple cross-checks, and a court order to ensure that the possibility of misuse of the detection technologies is minimized.

What’s more, the detection technologies don’t “read” or understand messages. They just look for matching patterns. For known CSAM, detection technologies use a database of hash value to identify a match. Detection of new CSAM involves the use of AI technologies that has been trained to differentiate new CSAM from legal material. The AI technologyies flags potential CSAM content for manual review before any further action.

5. Conclusions

In summary, EDRi’s criticisms of detection orders are as follows: firstly, it questions the technologies required for detection orders, arguing that existing technologies for detecting all three types of CSAM content aren’t accurate enough and would produce false positives. False positives could lead not only to the deletion of a user’s online account, but also potentially to an investigation of the user. Secondly, the enforcement of detection orders would fundamentally undermine E2EE, and would be a violation of users’ privacy rights. Thirdly, current CSS technologies that enable detection in an E2EE environment require scanning of all content on the user’s device, which could have a serious chilling effect.

Although ECLAG responded to criticisms a year after EDRi published its report, its response appears somewhat weak: ECLAG emphasizes the high accuracy and widespread use of existing detection technologies but fails to provide any independent verification of the accuracy of these technologies or address the concerns about CSS. In response to concerns about the unleashing of mass surveillance, ECLAG merely emphasizes the reliability of the detection technologies and the strict procedures for issuing detection orders.

As non-experts, it can be difficult for us to determine if there is a technology that can effectively balance the prevention of online child sexual abuse and the protection of privacy. Even if experts can prove that such technologies exist, the ongoing debate between opponents and supporters highlights a trust crisis. If EU citizens question the potential for EU authorities and tech giants to misuse power and infringe on privacy, this would become another complex issue.